Translation Matters – Part 3

This is the third and final installment of a brief series regarding translation matters. Because, well, translation matters.

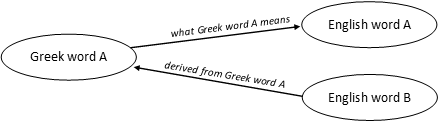

To summarize, the issue pertains to whether a certain Greek word in the New Testament (we’ll call it Greek word A) should be translated into the English word that carries the meaning of Greek word A (we’ll call it English word A) or an English word that was derived from Greek word A (we’ll call it English word B).

Perhaps that was wordy for you, and you would prefer to see it presented visually in a graphic:

The examination at hand is whether Greek word A should be translated as English word A or English word B.

As stated in the prior installments, I would suggest that Greek word A should be translated according to its meaning (English word A) and that translating Greek word A as English word B can cause misguided understanding to the English reader.

In the first installment, I provided a couple examples of slight consequence (martyr [“witness”] & aggelos [“messenger”]). In the second installment we looked at examples that prevent us from fully appreciating the impact of the believer’s new identity (christos [“anointed”] & baptizo [“immerse”]).

Let’s now look at an example that is a bit more egregious to show the potential severity of the issue.

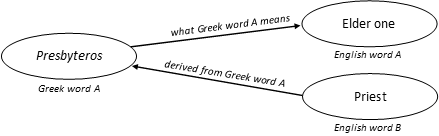

PRESBYTEROS

Presbyteros is the Greek word that means “elder.” It refers to a person who is older than others and, presumably, more mature; someone who is experienced in life and seasoned with wisdom.

However, the English word priest was derived from the Greek word presbyteros. Whether presbyteros is translated as “elder” or “priest” is extremely significant!

Certain Catholic versions of the Bible translate presbyteros as “priest”, whereas most Protestant-based versions translate presbyteros as “elder.” Which version a person reads dramatically affects their perspective of church hierarchy and leadership.

A Catholic reader of an English translation will read the Bible and naturally find justification for the Roman structure of the priesthood. To the contrary, a Protestant reader of an English translation will read the Bible and find justification for an elder-led church structure. They both are reading a translation that reinforces their predisposed bias.

When Paul and Barnabas traveled through Asia Minor establishing communities in Christ, they backtracked through all the towns and…

…And when they had ordained to them priests in every church… (Acts 14:22a Douay-Rheims)

…When they had appointed elders for them in the various churches… (Acts 14:23a NET)

Depending on the translation they either ‘ordained priests’ or ‘appointed elders’. That is a huge difference! How we read this verse entirely affects our perception, and it establishes precedent for the remainder of the New Testament as it relates to church government. It is not merely of minor consequence whether presbyteros is translated as English word A or English word B.

Many of you reading this are probably from a Protestant background and think ‘Surely this is an issue relegated to Catholicism; it’s not something Protestants need to be concerned with.’

Oh, no?

I think it’s time to turn up the heat a little.

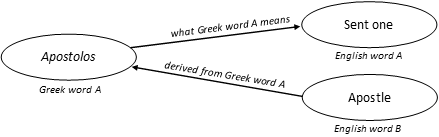

APOSTOLOS

The Greek work apostolos means “sent one.” It refers to a delegate, or a messenger (as one who has been sent forth with orders). The English word apostle was derived from apostolos.

The traditional definition of an apostle is confining. According to Thomas Schreiner:

“In a narrow definition of the term, the gift of apostleship is restricted to those who have seen the risen Lord and have been commissioned by him. Clearly, the twelve apostles fit these qualifications…” (<em>Spiritual Gifts</em>, p.26)

Agreed. The twelve do meet these qualifications. It’s also agreed that this definition is quite narrow. The traditional definition of the term apostle does not match with the Biblical content. Schreiner, a conservative theologian, acknowledges this contradiction:

“The apostolic circle isn’t limited to the Twelve … it is quite clear that James, the brother of Jesus, was also an apostle … A few others may have functioned as apostles … including Silas and Barnabas … Andronicus and Junia are called apostles…” (<em>Spiritual Gifts</em>, p.26-27)

Tradition states that an apostle is this, the Bible demonstrates that an apostle is that. What is going on here?

Well, there is a lot more that can be said than what will be addressed here and now; we’ll let that wait for a later time. For now, we’ll stick to the specific problem at hand.

Part of the problem is that in modern Christianity we largely fail to recognize what the true function of a “sent one” was in the First Century. We commonly view apostles like they were some kind of super-pastor, the highest level of church leader.

The reality is that the function of a “sent one” was very different from that of a pastor/shepherd. Those who shepherded in the First Century were the elders in their local communities. The function of a “sent one” was that they were, well, sent.

Sent ones, like Paul, were about establishing a community of Christ in each locality. They often traveled. They entered a town, preached the good news, gathered together those who received the message of good news, established them in the faith, and then they left to do the same in the next town.

They left permanent residents of each locality to shepherd and provide spiritual care for the gathering of the saints. But the ministry of the sent ones was one of grueling travel that resulted in many trials and conflicts.

Those who were called apostolos were so because of their function. That’s why Barnabas was described an apostolos (Acts 14:14). He functioned as a sent one. The emphasis of an apostolos was more about function and not pertaining to a hierarchical position in church structure. The function of an apostolos was one of itinerant ministry.

Apollos performed itinerant ministry. Originally from Alexandria, Apollos ministered in Ephesus. He spent significant time in Corinth and left to labor elsewhere. Apollos was also apparently in Crete. Paul referenced Apollos as an apostolos (1 Cor. 4:9; cf 1 Cor 3:22, 4:1, 6).

Paul referred to James, Jesus’s half-brother, as an apostolos , as well as Epaphroditus (Ph. 2:25) and Silas and Timothy (1 Thess. 2:6). There were traveling unnamed brothers who were called apostolos (2 Cor. 8:23). The writer to the Hebrews even referred to Jesus as apostolos (Heb. 3:1).

Because of the common use of the term apostle, when we read it in the New Testament we automatically think of the twelve. However, it prevents us from properly understanding the role of an apostolos and how they functioned (as a delegate, messenger, or one who has been sent with a purpose).

The twelve initially stayed in Jerusalem. It doesn’t appear they did much traveling in the early days. Perhaps they traveled throughout the neighborhoods in Jerusalem; that could be what they were doing in Acts 5:42.

Regardless, they did eventually go out to other regions. Peter had connections with believers in northern Asia Minor (1 Pet. 1:1). John was later involved in Ephesus.

Those in contemporary churches who use apostle as a title or an office are claiming an authority, prestige, acclaim, etc., that was not consistent with what it meant to be a “sent one” in the First Century. If they continue to preside over a particular congregation, they are not putting into practice the function of traveling, itinerant workers laboring from one locality to the next either attempting to lay a foundation of Christ or build upon one that has already been established. The function of an apostolos is not to remain stationary.

By translating apostolos as apostle, we lose the meaning of the function of an apostolos and replace it with a distorted understanding that apostles are some kind of Super Christians. We are indwelt with the same Spirit that indwelt the twelve. We often regard Paul as the greatest apostle, yet he described himself as the chief of all sinners. The apostles are not above us; we and they are on the same plane. The difference is that they functioned as sent ones spreading the message of good news from town to town, laboring to establish a local presence of Christ or build upon one that had already been established. If there are any people who are doing this today, they are functioning as apostolos.

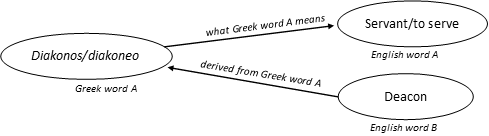

DIAKONOS

While we’re on the topic of church structure, let’s tackle the Greek work diakonos.

Diakonos means “servant” and is utilized with very broad usage. It is applied to servants of various kinds; to those serving a master (John 2:5, 9), to earthly authorities (Rom. 13:4), and to followers of Christ (John 12:26). It is even applied to Christ Himself (Rom. 15:8). Paul tells Timothy, an elder, that he will be a good diakonos if he puts “these things before the brothers” (1 Tim. 4:6). Paul refers to himself as a diakonos (Eph. 3:7). Even the ministers of Satan are diakonos (2 Cor. 11:15). The disciples were instructed to be a diakonos to one another (Matt. 20:26).

The noun diakonos appears 29 times in the New Testament. For all but three or four of these occasions most translations use servant (or attendant or minister). The verb form, diakoneo, appears 37 times; similarly, all but two are typically translated serve/serving or ministering.

Therefore, 90+% of the time, diakonos/diakoneo is translated according to English word A. For the handful of times the word is translated deacon (English word B), it is frankly quite questionable. I would suggest the translation of deacon is the result of the traditional bias of Western church structure.

Let’s look at the two uses of the verb diakoneo in 1 Timothy chapter 3:

And let them also be tested first; then let them serve as deacons if they prove themselves blameless. … For those who serve well as deacons gain a good standing for themselves and also great confidence in the faith that is in Christ Jesus. (1 Timothy 3:10, 13 ESV)

The most simple and appropriate translation of diakoneo in verse 10 is “serve.” However, forcing into the text the predisposed bias of Protestant tradition and church structure, “deacon” is unnecessarily used in English translations. “Let them serve as deacons” is far too convoluted when all that needs to be said is “serve.” More appropriate would be:

“Let them be tested first, then serve if they prove themselves blameless…”

Deacon does not even need to be present. And why utilize both the English verb “serve” and the noun “deacon” to translate a single Greek verb? Using both betrays the original Greek text. The King James Version is even more egregious:

And let these also first be proved; then let them use the office of a deacon, being [found] blameless. (1 Timothy 3:10 KJV)

“Let them use the office of a deacon.” Eight words! They stretched it out to eight words to force an insert of the office of a deacon, when a single word, “serve”, would have been adequate and appropriate. The Greek text has no element of “office” present. Again, diakoneo is a verb! Yet to substantiate the office of a deacon, both office and deacon are inserted in the English translation. Both terms are nouns although the Greek term is a verb, and the Greek verb is already being represented by the word serve. No other terms are necessary.

Argh! I should stop now before I get too fired up.

TRANSLATION MATTERS

The point of all this is that translation matters. It matters because far too often modern thinking and ways of doing things can force the hand of translators to offer a translation that validates the traditional church setting instead of allowing the text to speak for itself. If we allow the text to speak for itself, we may come to some very different understandings regarding Christ, his church, and who we are in him, than what we find in many English translations.

So let us pay special attention to recognize when English word B is utilized in translation, so that we prevent from falling into the trap. Doing so will allow us to emphasize what the New Testament authors actually intended.

Our proper understanding of the Bible depends on it.

Lord, teach us your ways accurately; without the bias of tradition, without the bias of translation. That we may know you rightly, so that you may be glorified in us.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

and I will continue to make it known,

that the love with which you have

loved me may be in them, and I in them."

(John 17:26)