This is the first of a brief series regarding translation matters. Because, well, translation matters.

This particular translation matter is one that has caused significant confusion over the centuries for English readers of Scripture. The severity of its danger is not solely about the proper translation of a single Greek word. It is a concept, a pattern, that can apply to the translation of numerous Greek words. Allow me to explain the issue at hand.

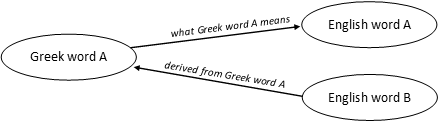

Let’s take a Greek word in the New Testament, any Greek word, it doesn’t matter at this point. Let’s call it Greek word A. Greek word A means English word A. But let’s say there’s also English word B which was derived from Greek word A. Typically, English word A and English word B are related, but are not synonymous.

Here’s the big question: when Greek word A appears in the New Testament, should it be translated as English word A or English word B?

English word A is what Greek word A means. Therefore, should Greek word A be translated as English word A?

However, English word B is derived from Greek word A. Without Greek word A, English word B wouldn’t even exist!

So which is it? Should Greek word A be translated according to what it means, or should it be translated into the English word that was derived from the Greek word? Perhaps you’ve drawn your own conclusion already.

Some of you will suggest that the context of the passage will determine which word to use. Very good point! Context is indeed a very important aspect of the text. Without context, we can’t truly grasp what is being expressed.

However, because of terminology we’re already familiar with, we may be led to insert an incorrect context. We may determine the context based on our prior bias from the terminology we use. Therefore, relying on the context doesn’t necessary solve anything for us. We could be inserting a faulty context because of the words we’ve learned to use in certain situations.

Perhaps I’ve rambled for too long and should get on with providing examples that are more specific. Before I give away the punchline as to whether English word A or English word B is the preferred answer, let’s start with a couple examples that are of only minimal consequence. As we continue to move forward, I suspect you’ll come to find that there can be quite serious ramifications if the wrong word is selected.

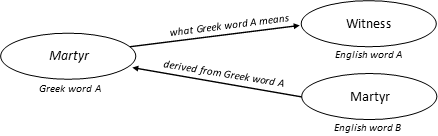

MARTYR

Let’s discuss the Greek word martyr. The Greek word means “witness.” I’m sure you can tell what English word was derived from martyr. That’s right, martyr. (A brain buster for you, I know.)

So here’s:

- Greek word A: martyr;

- English word A: witness;

- and English word B: martyr.

When the Greek word martyr appears in the New Testament, should it be translated as “witness” or “martyr”?

Here are a few examples of the Greek word martyr in the New Testament:

Then the high priest tore his clothes and said, “Why do we still need witnesses? (Mark 14:63 NET)

This Jesus God raised up, and we are all witnesses of it. (Acts 2:32 NET)

Pretty clearly, in these cases “witness” is an appropriate translation. It is not suitable in these instances that the Greek word martyr should be translated in English as martyr.

Imagine the Scripture stating: “Then the high priest tore his clothes and said, ‘Why do we still need martyrs?’” No, this doesn’t work. All the high priest needed was witnesses, not martyrs.

And perhaps: “This Jesus God raised up, and we are all martyrs of it.” Well, the apostles would end up being martyred, but that’s not what Peter referenced here. He was speaking of being an eyewitness of the Resurrection of Jesus.

Therefore, in these cases, translating as martyr (English word B) is not appropriate. In which cases might it be appropriate?

‘And when the blood of Your martyr Stephen was shed, I also was standing by consenting to his death, and guarding the clothes of those who were killing him.’ (Acts 22:20 NKJV)

“I know your works, and where you dwell, where Satan’s throne [is]. And you hold fast to My name, and did not deny My faith even in the days in which Antipas [was] My faithful martyr, who was killed among you, where Satan dwells. (Revelation 2:13 NKJV)

In both of these cases, martyr was translated in regard to a witness of God who died as a direct result. They were most definitely martyrs for the testimony of Jesus. But is martyr the appropriate translation of the Greek word martyr?

I would contend that Greek word A should be translated as English word A, and not translated as English word B. Using English word B inserts more into the text than what is the meaning of the original Greek word. Greek word A should be translated according to what it actually means: English word A.

It’s true that Stephen and Antipas were martyred for the Lord. Therefore, it seems so obvious to translate as martyr. After all, look at the words: martyr…martyr. Duh.

The point isn’t whether Stephen and Antipas were or were not killed for their testimony (they were!), the point is that the writer was describing them as a witness for the Lord. They were a witness unto death. In both examples, the rest of the verse informs us that they did indeed provide a witness unto death. But the point is that they are a witness; a witness who died for the testimony of Christ.

The problem arises when the translators pick and choose when to translate into English word A or English word B. And they’ll use context as the determination. However, using English word B brings in a distinction that may not have been the intent of the original author. The difference between a witness and a martyr is an English distinction, but the Greek word does not make that distinction; it means witness.

It’s just that certain witnesses end up being a witness unto death. Others don’t. But either way they’re all witnesses.

Selectively using martyr in certain cases gives the English reader a distinction that is likely not intended. The English readers perceive some as martyrs while others as merely witnesses. This is not a distinction made from the Greek. Christians may then think of witnesses as inferior to martyrs, but the point is that all believers are to be a witness for the testimony of Christ, whether their witness does or does not lead directly to death.

After all, Jesus was described as “the faithful and true witness” (Rev. 3:14). Certainly, Jesus was the greatest martyr for God of all. But Jesus came to provide a witness of the Father; a witness unto death. The Greek word martyr is about providing a testimony of the Lord, as a witness, whether as a witness unto death or as a witness not unto death. Either way, a witness. You and I, dear believer, are likewise witnesses.

‘Okay, Chuck,’ you’re likely thinking. ‘You’re really nitpicking about this, whether a witness who died for the testimony of the Lord is regarded in the Scriptures as a witness or a martyr.’

Fair enough. But I told you at the beginning that this was an example of minimal consequence. Before we look at some of the more serious cases in future installments, let’s look at another example of somewhat lesser consequence.

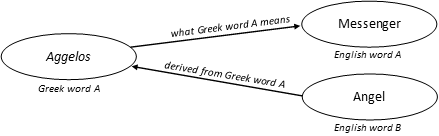

AGGELOS

Perhaps you don’t immediately recognize the Greek word aggelos. But when I tell you that double-Gamma (what looks to us like double-g) is pronounced using an ‘ng’ sound, then it should become obvious.

Aggelos means “messenger.” It refers to one who heralds a message. The English word “angel” is derived from aggelos (remember, the double-g makes “ng”). Angel, of course, is used regarding a heavenly being who does God’s bidding. All angels are aggelos (messengers), but not all aggelos (messengers) are angels.

Humans can also be referred as aggelos, such as:

- John, who baptized (Mark 1:2)

- John’s followers (Luke 7:24)

- Those Jesus commissioned to precede Him to Jerusalem (Luke 9:52)

- The messengers Rahab protected (James 2:25)

Also, Paul’s thorn in the flesh was “a messenger of Satan” (2 Cor. 12:7). The theophany of the burning bush was also aggelos (see Acts 7:30, 35).

In English, we have a distinction between heavenly and human messengers. Heavenly messengers we call angels; human messengers we call …uhh… messengers. We can often tell from the context whether the messenger is from heavenly or human origin. There’s little dispute here.

Where there is dispute is when the context is vague. So, in which passages is the context of aggelos vague? Where is it unclear whether the aggelos is of human or heavenly origin? Let’s look at the messages to the seven ekklesias in Revelation chapters two & three. (Side note: the translation of ekklesia as “church” is a whole different breed of egregious translation matters.)

“To the aggelos of…” (Rev. 2:1, 8, 12, 18; 3:1, 7, 14). It is unclear whether this is intended to refer to a human or heavenly person. This is when translating with English word B can cause significant damage.

When an English reader sees that the opening phrase of each of these seven messages is addressed to an angel, the immediate assumption is that each of these seven messages are being addressed to heavenly beings. This impacts our theology. This changes the way we view how God operates.

We may be led to conclude that God must have an angel designated to oversee each gathering of the saints. Or perhaps an angel over every city. I don’t know whether any of this is true or untrue. But translating aggelos as “angel” gives us this impression.

This is why it would be more appropriate to translate aggelos in these passages with English word A, what aggelos actually means: messenger.

Perhaps in the First Century AD, each city or neighborhood or group of people had a person who functioned as a messenger, as a herald. Sort of like an intermediary to pass messages to and from other localities. That’s how news would spread back in the day. A delegated messenger would take news from one locality to another. And then that locality’s designated messenger would pass the news along to the next locality. If anything like this was the case and was the intended use of the term aggelos, then angel is a very misleading translation.

Whether these messages in the Revelation were addressed to human or heavenly beings, translating as “messenger” works fine and is appropriate either way. But by translating as angel, it is potentially misleading. That’s why translating with the word that carries the meaning is more appropriate and to be preferred.

Even if every instance of aggelos in the New Testament was translated “messenger” we could still often determine from the context whether this messenger was a human or heavenly being. But when English word B is used, it reshapes our expectations of the passage based on our prior understanding of what an angel is.

Again, this is not of any terribly great consequence. But it’s the principle that matters because there are other examples that do result in more serious ramifications.

In the next installment, we’ll start looking at a few examples that carry more impactful consequences regarding the danger of translating with English word B.